Alex Schultz, ERS

Zondits sat down with three members of the Metro Atlanta Youth Energy Corps – Zoie Moore, Gwyn Rush, and Jo Studdard – to learn more about how energy efficiency relates to racial and social justice.

What is energy equity?

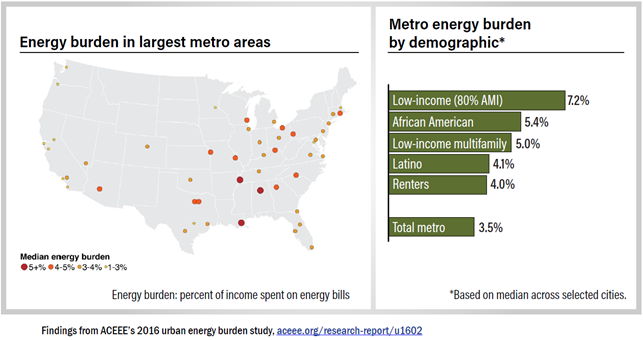

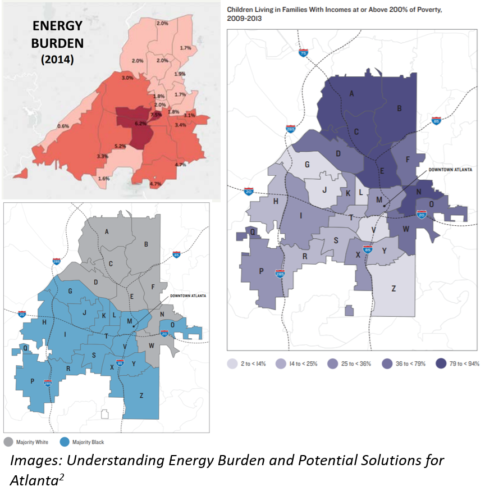

Gwyn: The general definition for energy equity means a fair distribution of the benefits and burden of energy production and consumption, which is very broad, but there are many different ways that you can measure it. We focus on energy burdens specifically – the percentage of your household income that you’re spending on your energy bills. If you look at Atlanta, we’re the third highest energy-burdened city in the country. On average, low-income Atlantans spend about 10% of their income on utility bills, which is above the 6% threshold that is considered unaffordable. But this unfair distribution doesn’t just fall along lines of class, it’s along lines of race as well. So Black and Latinx communities are facing the brunt of the energy burden, meaning they’re paying a much higher percentage of their income on these energy bills.

Data from a 2016 ACEEE study illustrates this point. Nearly two-thirds of households experiencing a high energy burden are Black or Latinx, and the average energy burden of a Black household is nearly 2% higher than that of an average metro home.1

Zoie: Energy equity impacts everyone. Look at the three E’s: environment, energy, and equity. Everyone lives and pays bills on this earth, but due to energy inequity, some pay more for their bills than others.

What is MAYE Corps?

The Metro Atlanta Youth Energy Corps is a Metro Atlanta-based, youth-led team committed to implementing energy equity programs focused on youth leadership, racial and social justice, and local collaboration. You can learn more here.

The organization intends to implement youth-led retrofitting projects to address long-term energy needs of households through home repairs. MAYE Corps was awarded a $10,000 grant in January, which has been frozen due to COVID-19. Before the pandemic eliminated funding and made home visits risky, MAYE Corps was preparing to retrofit homes in high energy burden communities.

Gwyn: We were going to work with the Community Center of South Decatur to do a series of educational workshops about different issues, such as how to understand your energy bills or how the Public Service Commission serves the community, which are both things that greatly affect people’s lives but can be quite opaque from a normal citizen’s standpoint. As soon as we can, we plan to start doing retrofits in homes and working with the community center more directly. But right now we’re really taking the time to focus on how we can build our partnerships with other organizations in the area. We try to make sure that we’re fitting in and being most effective with the organizations that already exist.

Zoie: Our education/outreach team is mostly focused on our partnerships and collaborations with community organizations. We have been teaching the community about what MAYE Corps does and getting our name out there. We have been working on how we can best collaborate with partners – how they can help us and how we can help them.

MAYE Corps is also focused on community education and has launched an energy professionals interview project on social media.

Jo: Our hope through this project is to drive meaningful conversations with people to learn personal stories. We also hope to hear from people who have professional connections to careers in energy, renewable energy, and infrastructure. Something we really want to do here is highlight the stories of women, gender minorities, and especially people in those groups who are also people of color. We recognize that for women, gender minorities, and people of color, there are a lot of barriers to access to energy careers. Even though there’s a lot of opportunity, there are several ways these professional environments still aren’t the most hospitable to these groups. So we want to showcase success stories of people who are making it in those fields and hopefully encourage some of our younger followers on social media to think more about some opportunities there that might be viable for them.

What causes energy burdens?

Many factors contribute to high energy burdens, including inefficient homes, economic strain, policy, and energy consumption. Some of these factors are exacerbated in communities already facing other financial, social, and physical burdens, which can create an inescapable cycle of poverty.

Jo: One of the ways that we can approach energy burdens and try to alleviate the disproportionate impact on communities of color is by reinvesting in those communities. These communities are so often in areas that are impacted by Urban Heat Island. These people often have more difficulty getting to their places of work, which can limit their ability to make an income. They can be struggling with food insecurity as well. But these are all things that are fixable, that aren’t just energy, but are also touching on other aspects of the lives of people who are experiencing this burden.

Inefficient housing in Black and Latinx neighborhoods is a large contributor to the disproportionate energy burdens in those communities. A 2016 ACEEE study states, “For African-American and Latino households, 42% and 68% of the excess energy burden, respectively, was due to inefficient homes. For renters that number was 97%, meaning that almost all of their excess energy burden could be eliminated by making their homes as efficient as the median.”3

Zoie: I went to high school at Little Rock Central High (LRCH), which is known for the Little Rock Nine (nine Black high schoolers who integrated the all-white LRCH, located in an affluent all-white neighborhood in the 1950s). Today, the neighborhood is predominantly African American, and you would be surprised how, for such a historic area, the neighborhood is just not up to date. It is difficult to remodel in historic neighborhoods, so the buildings are old and need retrofitting, leading to low housing values. This is all too common for many predominantly black neighborhoods today, whose affluent white residents moved upon the influx of non-white residents (white flight).

How can we work toward energy equity?

Gwyn: Energy burdens and energy efficiency both have clear solutions to save money and help the environment; most other sectors have a harder time making that argument clear. If your energy bills are lower, you’ll save money, which is great. You’re also reducing the amount of energy that you’re using, which is reducing carbon emissions, which is great. The equity aspect comes into play if you’re focusing on the communities that need it most, meaning you’re helping break generational cycles of poverty and possibly improving people’s health. In so many ways, focusing on energy equity is imperative. It addresses all three components of sustainability (people, profit, and planet), which is harder to argue for in some other environmental issues.

Jo: I am a lifelong renter as an adult. For the most part, unless you’re a homeowner, you generally have very little agency in choosing where your energy for your home is going to be sourced from. So I would really love to see greater options for renters including some renewable options on the table. When talking about energy equity, we keep coming back to this question of agency. I think that the most impactful solution would be to return that agency to the consumer. And, hopefully, as we move forward, the people who are impacted most by this issue will be able to see some of that power put back in their hands, and be able to help solve this massive problem.

Zoie: Energy equity ties into everything. That’s why I love seeing this energy justice movement so much, because it involves politics, race, Earth, gender. Everything is another reminder of how far we have to go. Whatever you’re passionate about, you can definitely find a connection to the environment.

Gwyn: I would love to see energy efficiency companies not only continue the work they’re doing now but also think about how they can use their role as energy efficiency leaders to start making communities more equitable.

Meet the Interviewees

References

- Georgia Tech, “Understanding Energy Burden and Its Potential Solutions for Atlanta,” https://www.scheller.gatech.edu/centers-initiatives/ray-c-anderson-center-for-sustainable-business/docs/EE-Phase-1_4-13-18.pdf.

- ACEEE, “‘Energy Burden’ on Low-Income, African American, & Latino Households up to Three Times as High as Other Homes, More Energy Efficiency Needed,” April 20, 2016, https://www.aceee.org/press/2016/04/report-energy-burden-low-income.

- Ariel Drehobl and Lauren Ross, “Lifting the High Energy Burden in America’s Largest Cities: How Energy Efficiency Can Improve Low Income and Underserved Communities,” ACEEE Energy Efficiency for All – April 2016 issue, https://www.aceee.org/sites/default/files/publications/researchreports/u1602.pdf.